Prologue: Goldsmith’s College, London, is

122 years of age. While Slade, an equally mature London art school is 145 years

old. The School of Fine Arts, Canterbury, has been in continuous operation for

130 years.

The globally omnipresent mythos of ‘not enough’ and its just-as-ubiquitous economic-nostrum

(the austerity-cure) are widely subscribed-to dogma. Pure belief: unassailable

faith in the primacy of monetary capital creation -

over and above every other human enterprise. I would suggest the monomaniacal

pursuit of statistical GDP, expressed as the one-eyed reapportionment of

existent public capital, to things exclusively charged with creating yet more

monetary capital, willfully disregards a raft of historically valued things -

things such as social/cultural capital. The big lie, the god of, Not enough and its philosophical

disregard, or write-down, of the historically high value, appreciated to the

arts and culture, heralds an ideologically blinkered period of social

engineering. Or, rather, a Dark-Ages 2.0, of social/cultural dismantlement to come.

A reactionary, faith-based, belief, that wills such wanton dismantlement, requires blind faith, faith that a fictionally over-spent

(actually reapportioned) public purse is the root cause of, and rationale for, reducing

whatever corporate-captured politicians want to characterize as budget-stretching

cultural frills. Rather than viewing time-proven arts as the foundational public

good they have historically been and are. As if forgettable business

enterprise, with its mostly symbolic, ephemeral, financial transactions are how

generations, now and in future, will ‘bank’ who they were, are, or may wish to

be remembered. And, perhaps, respected as something more than money-changers.

Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Krugman,

suggests the not enough dogma is, in

footnoted fact, the professed evangelical belief of self-serving privateers - their

synod being the ‘free-market’ Chicago School of economics. Privateers for whom

austerity is a religion and for whom the efficient, tax-structured, unregulated-and-tax-subsidized,

movement of publicly-underwritten wealth - from public to private hands - is an

article and act of faith.

My use of the trope ‘publicly underwritten wealth’ alludes to publicly financed

infrastructure such as: education, transport, government funded and regulated public

health & safety regimes, and government facilitated international trade …

among others – without which private business, high-income individuals, and international

corporate elite would not so easily prosper and accrue the massive cash reserves

they currently hoard.

Hard statistics show the cost-burden of

public-infrastructure – in the past number of decades – has shifted

dramatically from wealthy (corporate and private, high-earners) onto the middle-class

and working poor’s increasingly skinny shoulders. However, oddly enough, the relative

scale of received benefits, to the so-called middle class, and working poor, from

public infrastructure (affordable tertiary education, affordable housing, public-health

maximization, subsidized arts) have hardly been commensurate with the shifting

tax-burden they bear.

What has increased, however, is the volume

of sermonizing and numbers of sermonizers preaching the religion of public austerity

as catalyst for private profit. Preaching self-righteously of reduced

expectation, shared burden, hard realities and hard choices. Those preaching are

rarely, if ever, on the receiving end of tough-love prescriptions they propose.

In today’s silo-shaped, business-modeled,

universities there are austerity-pulpits aplenty – staffed by ambitious executive

administrators. The reallocation of public money in the tertiary sector has

similarly moved. Shifting from the long-admired public good of humanities, to academic

sectors populated with private profit-takers (or makers) depending on your

ideological point of view. Making universities, in essence, the exclusive

research and development arms of corporate manufacture and business.

The public’s money has been, and continues

to be, business-purposed away from the perceived ‘soft’ subjects of arts and

humanities. Intellectual disciplines, long-esteemed (in the course of human

history) as historically uninterrupted public testament to, and stores of,

intangible, but socially effective, human, virtue. Public education dollars –

diverted, re-purposed, reallocated, into amoral ‘business friendly’, hard subjects; such as engineering and

science. ‘Hard-discipline’ vocational areas, at Canterbury, are awash, as I

write, with actual, un-spendable surpluses - while just across campus, programs

and students, of arts & humanities, go to bed ‘hungry’. Colleagues in

Engineering, I should note, are just as scandalized by the economic disparity

and surplus.

City centers, municipalities, regions, and

nation-states (driven by the power-elite’s appetite for the arts-as-entertainment

and as civic status-symbol) still budget, subsidize, and vie with geopolitical

rivals, for ‘the arts’. But now, our universities - originally designed as a kind-of

creative castle-keep, sanctuary, for creators of intangible but recognizably

valued ideas and objects - increasingly seek to divest themselves of their

historical charge, and, in the place of so-called pure-knowledge-creation, seek

exclusively to harbor, and further, what executive administrators (and their

political overlords) see as bankable, mercantile, technical enterprise.

Of course some skeletal ‘core’ arts and

humanities will be retained; served to the student body, as a side-dish, as a garnish,

as a way to provide jumped-up ‘wealth creators’ with a ‘core’ understanding of

socially recognized cultural markers of class-gentility … providing future

‘masters-of-the-universe’ with a feel

for the arts. For even the university-as-a-business understands the importance,

or at least class-desirability of, gentrifying, with the help of the arts, the scions

of commercial wealth it helped nurture. Nurture with public money.

University-as-a-business understands, of

course, that at the end of a long day of business enterprise, even a self-starting,

hard-charging technocrat, or captain of light-industry, wants to let his

(mostly His) hair down … with a little help from (in proper time-and-place, of

course) cultural ‘long hairs’. I mean, really,

what would all the toil of business-innovation, and its attendant commerce,

really amount to without the house on the hill. The hard-earned place in the

world where one repairs: to regard one’s trophy plastic arts – on one’s expansive

white wall – to thumb an anthological volume of verse, purchased in one’s youth

for the Uni. literature-survey course, to cue the Schubert impromptu one became

familiar with in music appreciation 101.

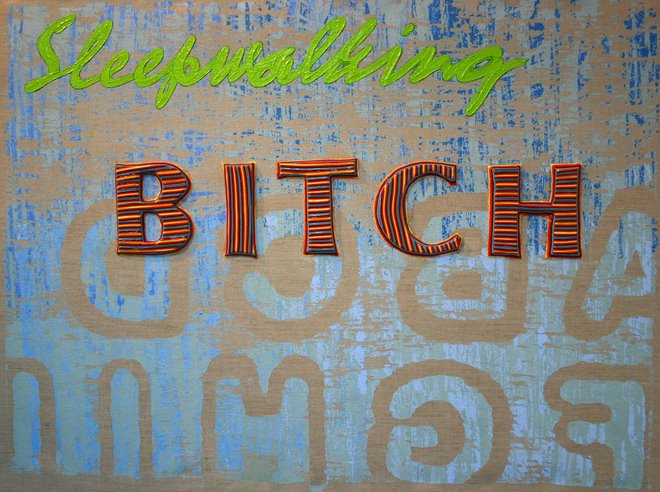

Now what is this essay, so far, but a

collection of allusive generalizations, without specific, local, examples? Or, for that matter, international examples.

Here’s now is a regional specific.

Something plucked, from an overgrown farm-service town, on the Canterbury

plains – laid up against two, much more metropolitan, examples: Goldsmith’s

College, London, is 122 years of age. While Slade, an equally mature London art

school is 145 years old. The School of Fine Arts, Canterbury, has been in

continual operation for 130 years.

130 years of unbroken existence would have had

The School of Fine Arts’ generationally-sequential overseers – our Aotearoan

ancestors - seeing fit to preserve, to allocate, truly scarce resources to, an art school (no less) through two

world wars, countless nation-state police actions, domestic political regimes

and social upheavals, at least one (if not putatively two) great depressions and

inestimable numbers of financial recessions and economic reversals.

Given the current faux-austere Canterbury University,

and ruling government, mood, the institutions’ managers may well be thinking,

here and now, that our feckless forerunners – generations of responsible art

school preservationists - were simply naïve, antiquarian in thinking, forever,

somehow, behind the times, out-of-step, devoid of forward-thinking, hard-headed

business ambition and business-drive. Or we might consider that in the place of

purchasing yet another bloody, cold, potato (or artillery shell, for that

matter) the preservationists thought to buy, instead, a fucking paintbrush.

Kiwis are preternaturally interested in the

Mother Country, in its doings. Now, one

might ask, what do you reckon the U.K., London, its good Burghers do, if a passel of Neo-Liberal razor-boys

sought to slice away – with all the finesse of a whale flensing gang - at the health,

prestige, and prominence of its longest-lived (Slade & Goldsmiths) art

schools. Of schools, who like Ilam, are thought to be, in significant part,

responsible for the nation’s most recognized names in national and

international visual arts?

Shall I make another comparison? Or will

that one do?