"An artist has apologised for upsetting the family of a

murder victim after the killer's portrait was entered in a

national art award.

The artwork, showing Christchurch murderer Helen Milner -

dubbed the Black Widow - is one of 49 on display at the

Wallace Arts Centre in Auckland."

No

better place for a crucifixion than the wall of a public exhibition

space.

If the photo of my father/brother/child's (God forbid) murderer may be used to sell newspapers and television commercials then it certainly may be grist for

artwork.

For some perspective on this, imagine someone protesting (as

unseemly) the depiction of a criminal (or criminal act, no matter how

ghastly) in a fictional or documentary work for page, screen, or stage.

That sort of objection would strike most as censorious and socially ultra-conservative.

But painting, in the 21st century, is somehow still expected to bear the

burden of Victorian expectation - to be obediently enobling, elevating, and meaningful in

instructive ways.

Now, consider the murderous bloodletting in paintings such

as Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith Slaying Holofernes, or the confrontational

Beheading of Saint John the Baptist by Caravaggio. Or the infinite catalogue of

frank perversions depicted by various historical hell painters, such as Bosch.

However, in these tepid latter days, if one were to dare anything approaching the incitement

of works such as the aforementioned, the media would dine on the artist for weeks.

Oddly enough the argument I've just made rarely if ever gets made. It

is as if the history of images had never happened and we'd all been

moved (in our sleep) to Sinclair Lewis' Zenith.

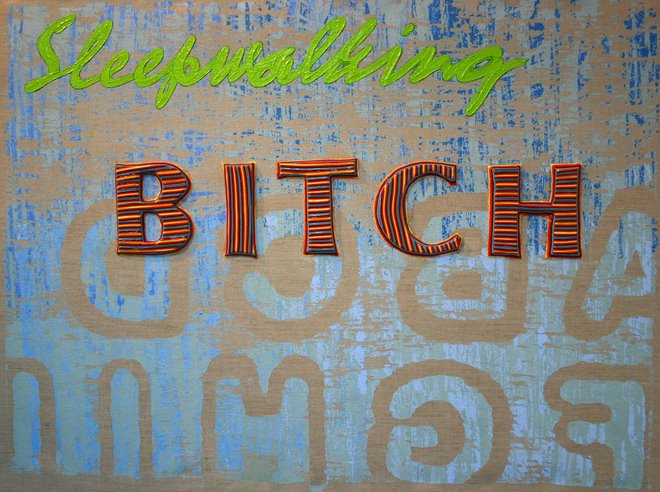

If there is a public conversation to be had about Mark Rayner's Black Widow it would be more entertaining, and instructive, to have an exchange (as Andrew Paul Wood did in my Facebook thread) about the similarity of strategy entertained by both Mark Rayner's Black Widow 2014 and Marcus Harvey's 1999 Myra.