Look

A picture is something that requires as much trickery, malice and vice as the perpetration of a crime, so create falsity and add a touch of nature – Edgar Degas

As an artist and an occasional writer I am, occasionally, asked to write about another artist’s work. I usually find myself responding reluctantly, willingly or enthusiastically. I won’t tell you in what situation or to which specific artist I will initially react this way but, when I take up the offer, it is always because I like the work, something it suggests or both. I’m never sure why I’m asked. Is it because whoever is asking likes the way I write or is it the expectation that, being an artist, I’ll at least know what I am writing about? I’m hopeful it’s the former as while I do know something about art, it’s not that simple.

The first difficulty is, as an artist, I usually have little idea of what I’m doing and no idea how others will respond to the finished work. I expect its much the same for most other artists. This difficulty is further hampered by a reader’s desire for meaning. A reader often assumes if someone has bothered to write about the work it must have specific meaning. This is a major difficulty, not only in most instances, but particularly in this one, as I know how much Roger Boyce dislikes meaning. I’m not adverse to meaning but I know what Roger means. The search for meaning clouds the looking. The desire for meaning can not only hamper viewing but also making. I would suggest, if an artist’s singular intention is for the work to be meaningful, it will never reach the studio door. As the artist will be so weighed down by their objective they will never complete anything.

For the critical viewer the over-arching desire to find meaning can obscure any, albeit unintentional, utilitarian meaning. It is a desire that often approaches apophenia. Apophenia is the tendency to mistakenly perceive connections and meaning between unrelated things. Admittedly, art often makes connections between unrelated things. Surrealism is an obvious example. In fact, the bringing together of the seemingly unrelated is the foundation of surrealism and it is an idea that still underpins the bulk of contemporary art practice. The apophenia I am thinking of is more akin to the mis-heard. The song lyric sung over and over in your head in such a way that it has acquired personal meaning. Then, at a later date, you see the lyrics printed and realise they are completely different from what you thought you heard. While the meaning you have gained may remain, it was never in the original. If this happens when viewing or writing about art, what is misread, either through a cloud of ideological preconceptions or the willful desire for meaning, enters a world of Chinese whispers. Eventually the thing looked at and its imposed meaning bare no relationship to each other. You often see evidence of this in gallery wall labels where the desire to imbue meaning is paramount.

Do these paintings need words? Words can either facilitate or obstruct understanding. Do any paintings need words? What you see, is what you see. And what you see, is what you want to see. As William Burroughs said “You can't tell anybody anything he doesn't know already”. Is it necessary to read a script before seeing a movie, see sheet music before listening to a song or to look at illustrations to understand a novel. Those distractions may be interesting in themselves but are they primary?

These days, with visual art, words seem to be a requirement. Yet, scholars inform us, that only a few centuries ago, paintings were used to tell stories to those who couldn’t read. Hence, the early development of the visual language of western art was largely within the confines of the church. After all, seeing is believing. Now it’s as if, we can’t engage with an artwork without having to read something, either before or after viewing. Is it really that difficult? That complicated? Was it early last century, with the rise of abstraction, that words became pressingly necessary? But there has always been abstraction. It wasn’t new. You only have to look at aboriginal or Islamic art to see that. And, what is perhaps the most abstract art form of all, music, is widely considered to be so immediately understood it easily crosses cultural boundaries. So, it seems we believe what we hear. Why is it we no longer believe what we see?

How do we see visual art? It appears initial engagement is subliminal. A subtle, oscillating, mix of thought and emotion stimulated by visual cues. A recognition. An experience that may build slowly or occur before you know it. The work will either appeal or not. If it doesn’t appeal there is no obligation to take it any further. You don’t have to understand why you didn’t like it or found it unusable. If you have responded favourably to the work’s visual stimulus and are intellectually curious you may want to know more. Even if it is just to know exactly what that shade of white is because it would be great on your bedroom walls. Like most everything else, natural or manufactured, an artwork can be dismantled. Its parts be can laid out, identified and their function analysed but by then the patient is probably dead. This kind of investigation is only suitable for artists.

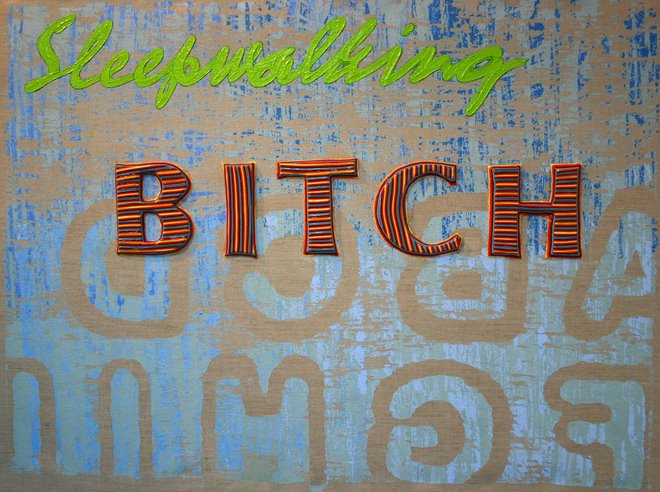

With his paintings Roger Boyce wants the viewer to look. To believe what they see. He implies this by painting paintings of paintings. There is no smoke, it is just mirrors, and like a magician, who wishes to not only delight with his sleight of hand, he also wants to reveal how the trick was done. You will notice next to the painted paintings there are no wall labels. If it’s only meaning you seek, I would start here.

Robin Neate